Constellations of Shadows

Term

The term «constellation» has become an important tool for understanding how artworks can illuminate the relationship between past and present outside of linear historical narratives. Emerging from the writings of Walter Benjamin, a constellation is not a progression but a configuration. It is a cluster of heterogeneous elements, such as images, gestures, histories, and voices, that gain meaning through their position in relation to one another. Contemporary art, especially that concerned with archives, memory, and political rupture, often operates through this non-linear structuring of time.

Relevance

In contemporary discussions of visual culture and art history the concept of the constellation appears as an alternative to linear models of development. Zdenka Badovinac argues that a constellation makes it possible to work with interrupted and multiple histories by creating horizontal fields of relations between fragments of archives aesthetics and memory. Although this theory originates in the study of post socialist art it can illuminate cultural processes in many other contexts.

Visual Archives and Parallel Histories between German Expressionism and Film Noir

The relationship between German Expressionism and classical Hollywood film noir can be understood as a constellation of visual strategies and thematic concerns that migrated, transformed, and re-crystallized across time and geography. Rather than treating influence as a linear transfer from Berlin to Los Angeles, it is more productive to conceive of both movements as discrete yet interlinked visual archives that illuminate one another. Their shared fascination with distorted space, fragmented subjectivity, and psychological destabilization suggests a parallel historical evolution shaped by social trauma and cinematic innovation. By examining specific films across both traditions — The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922), The Golem (1920), Warning Shadows — A Nocturnal Hallucination (1923), and, on the noir side, Double Indemnity (1944), Spellbound (1945), T-Men (1947), and Kiss Me Deadly (1955) — one can map a complex constellation of visual motifs that reveals how film noir reconfigured Expressionist codes into a distinct American idiom.

Early German cinema emerged from the psychological and material devastation of post-World War I Germany. The Expressionism responded to this climate with sharply angled sets, extreme chiaroscuro, and an emphasis on interior states externalized through spatial distortion. The jagged architecture of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari exemplifies this tendency. The painted shadows and twisted geometry articulate an unstable world that mirrors the protagonist’s fractured mental state. This is not merely stylistic excess but a visual grammar of national disorientation.

1 — «Kiss Me Deadly» 1955 Robert Aldrich 2 — «The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari» 1920 Robert Wiene

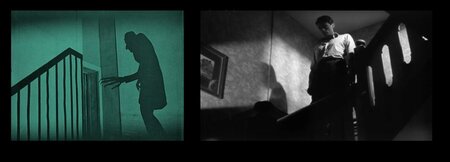

With the emigration of German filmmakers in the 1930s, these visual strategies entered Hollywood, where they encountered a different socio-historical context shaped by the Great Depression, rising urban crime, and postwar disillusionment. What results in film noir is not a direct continuation of Expressionism but a transformation. Noir reconfigures Expressionist motifs into a language appropriate for exploring moral ambiguity and psychological fracture within a realist American framework. The contrast is clearly visible when comparing the shadow-saturated alleys of T-Men (1947) to the supernatural menace of Nosferatu (1922). In Murnau’s film, the elongated shadow of the vampire functions as an embodiment of an external, otherworldly threat. In T-Men, however, the shadow of the murderer operates as an extension of the human psyche. The Expressionist demon becomes the noir criminal, and the supernatural is transmuted into interior moral darkness.

1 — «T-Men» 1947 Anthony Mann 2 — «Nosferatu» 1922 F.W. Murnau

The same constellation reappears in the shared interest in mediated violence. Warning Shadows — A Nocturnal Hallucination uses silhouettes to foreshadow future events, visualizing the protagonist’s terror through literal manipulation of projected shadows. T-Men adapts this technique to suggest violence without showing it. The scene in which a wife is murdered is conveyed solely through shadows on the wall, demonstrating how noir appropriates Expressionist opacity to represent moral corruption rather than metaphysical threat. The technique becomes a means of psychological evasion and repression.

1 — «Warning Shadows — A Nocturnal Hallucination» 1923 Arthur Robison 2 — «T-Men» 1947 Anthony Mann

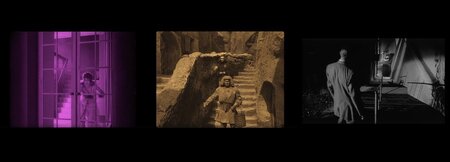

The films also share an architectural lexicon that shapes narrative affect. Expressionist cinema frequently uses staircases as unstable transitional spaces, as in The Golem or Nosferatu, where the ascent or descent marks the approach of danger. Noir reinterprets this motif to emphasize moral descent. In Spellbound, John Ballantyne descends the staircase in a trance, razor in hand, suspended between innocence and potential violence.

1 — «Warning Shadows — A Nocturnal Hallucination» 1923 Arthur Robison 2 — «The Golem» 1920 Paul Wegener, Carl Boese 3 — «Kiss me deadly» 1955 Robert Aldrich 4 — «Nosferatu» 1922 F.W. Murnau 5 — «Spellbound» 1945 Alfred Hitchcock

In Double Indemnity, Phyllis Dietrichson’s first appearance atop the staircase marks her predatory dominance, foreshadowing her role as a manipulative femme fatale. Across both traditions, the staircase becomes an axis of psychological and narrative tension.

«Double Indemnity» 1944 Billy Wilder

Light functions as another key node in this constellation. Expressionist films often confine the protagonist within isolated beams of light or heavy vignettes that emphasize emotional rupture. Noir adapts this technique by framing characters within architectural «cages» created by furniture, fences, or Venetian blinds. In Kiss Me Deadly, the bars of a bedframe trap the protagonist visually, turning a mundane object into a symbolic prison.

«Kiss me deadly» 1955 Robert Aldrich

Similarly, in Spellbound, the ticket-booth enclosure reduces the fleeing characters to silhouettes behind bars. These visual enclosures echo the Expressionist practice of isolating figures within geometric forms, but noir invests them with ideological weight, suggesting the inescapability of social structures and psychological compulsions.

«Spellbound» 1945 Alfred Hitchcock

Сonclusion

Taken together, these films form a constellation in which German Expressionism and film noir appear as parallel archives of visual and psychological inquiry. Expressionism externalizes internal conflict through stylized sets and supernatural figures, translating social crisis into visible distortion. Noir internalizes these same distortions, mapping them onto moral ambiguity, urban alienation, and the individual psyche. This reciprocal illumination demonstrates that the relationship between the two is neither derivative nor merely stylistic. Instead, both traditions articulate responses to historical trauma through analogous visual strategies that traverse national boundaries.

Ultimately, film noir does not simply inherit Expressionist techniques but reinterprets them to articulate a distinctly American cultural anxiety. The jagged landscapes of Caligari, the spectral shadows of Nosferatu, and the ritual geometries of The Golem reappear as the urban nightscapes of Double Indemnity, the psychological disorientation of Spellbound, and the paranoid brutality of Kiss Me Deadly. These films reveal how a shared visual lexicon can generate parallel histories, each shaped by its own social context yet linked through persistent aesthetic concerns. To view them as a constellation is to recognize the network of visual, thematic, and historical correspondences that illuminate the nature of cinematic modernity itself.

Грознов, О. История кино. 24 кадра в секунду. От целлулоида до цифры / О. Грознов. — Москва: Эксмо, 2024. — 400 с.

Заметки о фильме нуар // seance.ru — URL: https://seance.ru/articles/noir-notes/ (дата обращения: 05.12.2025).

Носовский, А. Н. Светотень. Истории, теории и практики / А. Н. Носовский. — Москва: Крупный план, 2024. — 384 с.

Орозбаев, К. Н. Кинематографические источники американского фильма нуар / К. Н. Орозбаев // КиберЛенинка. — URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/kinematograficheskie-istochniki-amerikanskogo-filma-nuar (дата обращения: 05.12.2025).

Склярова, Я. А. Традиции немецкого киноэкспрессионизма в американских фильмах нуар 1940-1950-гг / Я. А. Склярова // КиберЛенинка. — URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/traditsii-nemetskogo-kinoekspressionizma-v-amerikanskih-filmah-nuar-1940-1950-gg (дата обращения: 05.12.2025).

«Кабинет доктора Калигари» (1920 г., режиссер Роберт Вине)

«Носферату. Симфония ужаса» (1922 г., режиссер Фридрих Вильгельм Мурнау)

«Голем, как он пришёл в мир» (1920 г., режиссеры Хенрик Галеен и Пауль Вегенер)

«Тени: ночная галлюцинация» (1923 г., режиссёр Артур Робисон)

«Двойная страховка» (1944 г., режиссер Билли Уайлдер)

«Завороженный» (1945 г., режиссер Альфред Хичкок)

«Целуй меня насмерть» (1955 г., режиссер Роберт Олдрич)

«Люди Т» (1947 г., режиссер Энтони Манн).