Temporally Embodied Sound

Temporally Embodied Sound as Collective Experience

Temporally embodied sound is a term suggested by Colin Chinnery and presented in Glossary of Common Knowledge Vol. 1. It tackles the idea of environmental sound as a historical medium. Chinnery states that even though it is rarely considered as such, environmental sound, both natural and manmade, may contain as much information about specific time and place as any other visual medium, since the soundscape is defined by the context, is inseparable with the context, and changes with the context through the time. Environmental sound is embodied, meaning that it is perceived by hearing, body, memory, and emotions. Yet, the sounds are not documented by official histories and are only carried in the memories of people who heard them at the time. Thus, Chinnery puts emphasis on sound embodiment as collective experience, stating that environmental sound has the ability to make a group of individuals reconnect with their involuntary or emotional memories.

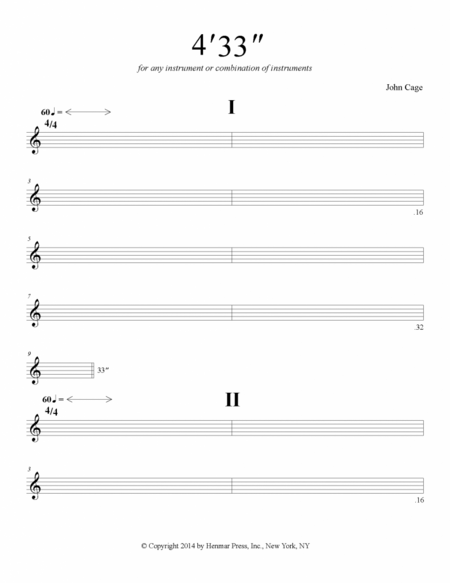

John Cage, 4'33'', 1952

An excellent example of temporally embodied sound as collective experience is John Cage’s world famous 4'33''. It is a musical composition where the performer or a group of performers remain silent for the duration, transforming environmental sounds into the music itself, shifting focus to the listeners' experience of their surroundings that only exist during the performance as part of their embodied consciousness.

Gleb Glonti, Giant Rhetoric of Excess, 2024

Another noticeable example of this concept is Gleb Glonti’s work. In Giant Rhetoric of Excess, Glonti creates a sound object consisting of packets of potato chips arranged in a cabinet. Essentially, this is an object being exhibited in a gallery, thus it is not to be touched. However, the rustling sound of a packet of chips is a striking, distinctive, and memorable element among the environmental sounds. Therefore, seeing the packets before them, the viewer connects with their own experience of interacting with packets of chips and, consequently, with the corresponding sound image.

Field recordings is one of the mainstream techniques in sound art. It is the most straightforward way to document the environmental sound and make it accessible for many. Pasvikdalen by Norway-based Jana Winderen is a clear example of this technique. Winderen collected both recognisable and unobvious environmental sounds during her expedition in the Pasvik Valley, travelling through Kirkenes (Norway), Nikel (Russia), and Zapolyarnyy (Russia). In her work, Jana Winderen creates on one hand a peculiar archive of sounds that the valley’s residents experienced at the time, a composition that they can connect with further on. On the other hand, this archive can serve as a tool for approximate historicity, meaning that Pasvikdalen cannot be considered an accurate historical archive in the strictest sense. Firstly, there is no established methodology for sound documentation that would allow sound to be treated as a historical source, so a sound archive is more of an artistic practice, falling within the purview of sound art. Secondly, a genre such as field recordings, including the aforementioned work, involves audio editing and processing techniques, compiling them into a single composition. While this is an effective method for creating sonic experience, it also calls into question the authenticity of the source material.

Temporally Embodied Sound as Personal Experience

It is crucial to emphasise that embodiment per se is always a personal experience. In accordance with psychoacoustics, all people would perceive certain sound similarly, but never the same, even in case of identical twins. However, in this chapter, I would like to reason on the topic of personal sonic contexts and the means artists use to document and transmit them to the public. I will overview two works by Anna Martynenko as powerful examples.

Anna Martynenko, Guests, 2022

As mentioned above, temporally embodied sound is closely related to the term archive. Working with sound archives can be a personal, embodied experience, despite the lack of a live, time- and place-based experience. Even though we intentionally listen to recorded sound, we still create our own embodied experience. Anna Martynenko reinvents the context of a Russian composer’s life and transmits it to the public. Guests is an artistic dialogue with Rimsky-Korsakov, who, as a synesthete, experienced musical keys as colors. Inspired by his perception, the artist gives tangible form to singers’ voices by translating them into sculptural casts. Each sculpture is shaped through synesthetic principles: vocal pitch determines the number of protrusions, vocal range defines the span of radiating arms, and coloratura informs the surface texture. The resulting forms blend objective acoustic properties with the artist’s own subjective, internal synesthetic impressions of each voice.

Displayed on empty chairs in the museum, once occupied by renowned singers, these sculptures evoke their lingering presence. The galleries seem filled with imagined sound and intangible motion, as if the voices continue to resonate despite their physical absence.

In this project, context plays a crucial role in activating the viewer’s inner ear. When the audience understands which vocal qualities are encoded in each sculpture and compares them side by side, they can mentally reconstruct distinct sonic images that would dramatically differ from individual to individual. Yet this cognitive process takes significantly longer than the familiar, automatic association between a visual object and its corresponding sound, as it is constructed in Gleb Glonti’s Giant Rhetoric of Excess.

Anna Martynenko, Empty Space, 2025

Empty Space is a site-specific art project that appear to be a series of sculptures. For creating those sculptures, a custom microphone array was developed to capture sound vibrations from multiple directions around a central point. Microphones were dispersed throughout the Garage Museum Workshops, recording ambient acoustics from every angle. From these recordings, a single, standout second was selected, either a vivid sonic event or a site-specific sound with a clearly defined structure. This one-second fragment was then algorithmically translated into a sculpture, where sound amplitude directly governed the degree of pressure applied to the form. The outcome is a three-dimensional 'cast' of airborne vibrations, a tangible visualization of sound at an exact moment in time, effectively a 'frozen instant'.

In this case, viewers cannot mentally replay the exact sounds captured in the sculpture simply by looking at it. Instead, they may only speculate about what those sounds might have been, informed by the installation’s location and context, for example during the artist talk. However, by imagining themselves at the sculpture’s position within the space, they can intuitively invent their own sound image, sense differences in loudness and spatial distribution, perceiving, through form, how sound energy varied across directions and distances, embodying the sonic experience through the viewer’s imagination and inner ear.

Conclusion

Thus, my interpretation of the term temporally embodied sound implies not only an interaction with environmental sound as a historical medium (which signifies the primacy of collective experience), capable of describing an era or evoking certain memories in the listener. It is not only the creation and manipulation of archives. All of the above certainly has its place. However, for me, it is important to emphasize that embodiment is also a significant aspect, as an active action of the subject, as a personal experience based on working with the inner ear and imagination. This idea is becoming increasingly relevant as the plastic arts develop in the context of sound art.

Chinnery, C. (2014). Temporally Embodied Sound. In Z. Badovinac, B. Piškur, & J. Carrillo (Eds.), Glossary of Common Knowledge (Vol. 1, pp. 26–27). Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana; L’Internationale.